John Bliss, 8/15/2025

The reactions to GPT-5 (released last week) have been deeply polarized. While it claimed the top spot on legal benchmarks and other evals, it generally holds only a narrow lead. As the first whole-number successor to GPT-4 (released more than two years ago), many expected a more revolutionary breakthrough. Some see this as a sign that AI progress is slowing. Others argue that the seemingly incremental gains fit on a steady, even exponential, trajectory of AI advancement. This post digs into the early data on what GPT-5 really means for legal AI—and what the available evidence (tentatively) tells us about the state of legal AI.

The Metrics

The headline improvements are significant by some measures. OpenAI reports the “Thinking” version of GPT-5 has an 80% lower hallucination rate than their previous best model (o3). They also claim record scores on coding and mathematics, including 94.6% on AIME compared to o3’s 88.9%. On “economically important tasks” across 40 occupations including law, o3 had scored 33.5 while GPT-5 is approaching the industry expert baseline (50) with a score of 47.1.

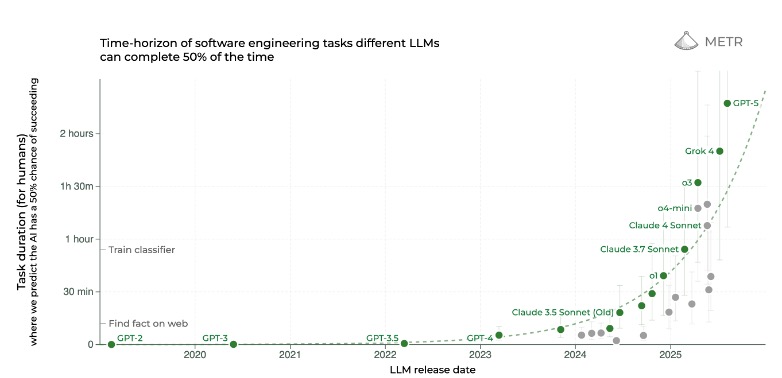

Some evals put GPT-5 on the exponential curve of AI progress. One metric considers the complexity of tasks a model can complete autonomously, as measured by human-equivalent time (i.e. how long the task would take a human expert). According to METR, this human-equivalent time has been growing exponentially over the past six years, reliably doubling every 7 months as pictured below. GPT-4 could only handle software engineering tasks that would take a human 5 minutes (at a 50% rate of successful completion). METR suggests GPT-5 can now complete tasks that would take a human software engineer more than two hours.

The initial evalulations have tended to overlook the state-of-the-art “pro” version of GPT-5. When it is tested, it appears to surpass other versions (GPT-5 “main,” “thinking,” “mini” etc.). On Humanity’s Last Exam (a PhD-level cross-disciplinary benchmark), the main GPT-5 model scored 24.8% while Pro jumped to an unprecedented 42%.

On law-specific benchmarks, the gains look similarly real but (arguably) modest: Vals.AI added GPT-5 to its LegalBench board last week and reports 84.6% accuracy, currently the best among 70+ models on their mixed set of legal reasoning tasks. Yet, this is only a 2-point bump over o3 (82.5%). On Harvey’s BigLaw Bench, GPT-5 scored 89.22%, roughly 5 points above o3.

A big advance for casual AI users

The real impact of GPT-5 might be less about pushing the ceiling of AI capability than about finally exposing the masses to the “reasoning revolution” of the past year. Many casual AI users were unaware that reasoning models (like o3) have been dramatically outperforming traditional LLMs—across benchmarks and legal RCTs and law-exam studies (with o3 scoring as high as A+ on law exams vs. B+ for non-reasoning models). Until now, the default when using most AI platforms, including legal AI platforms, has been non-reasoning models. Most users didn’t know to manually switch to the reasoning model for complex queries. Now, ChatGPT defaults to an “auto” mode, which routes each query to different versions of GPT-5, with the most complex matters routed to the reasoning version.

But significant disparities will persist. On OpenAI’s platform, the pro version of GPT-5 is only available to subscribers paying $200/mo. And sophisticated users will manually select their preferred models (on ChatGPT and other platforms where this option is available), while casual users may not even realize when OpenAI downgrades them to weaker models mid-conversation (though OpenAI has promised to add transparency about this in the near future).

So where does this leave us?

The jury is still out. Early metrics show significant improvements, but GPT-5 has yet to face the full gauntlet of rigorous legal testing, including RCTs, law school-exam studies, and LEXam scores (the new long‑form law‑exam benchmark built from 340 real exams). Researchers will need to examine the pro version of GPT-5 to shed light on the current frontier of legal AI capabilities. They’ll also need to shift from benchmarks to measuring real-world performance as these tools become embedded in daily legal practice. Amid all the hype and polarization, these empirical insights are more critical than ever.